Motion in a Plane

Motion in a plane

We can learn about physical quantities like position, displacement, velocity, acceleration just by knowing the path of motion. Path can be one dimensional (in a line), two dimensional or three dimensional. We shall learn to calculate motion in one dimension and we shall see that it is easy to extend it to two and three dimensions.

Relevant quantities in motion of a body are position, displacement, vector and acceleration.

Motion in one dimension

Tracking Position

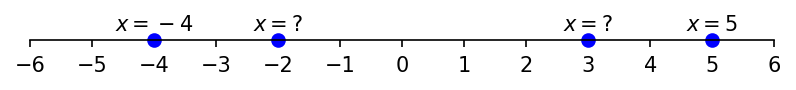

To track position of object in one dimension, we define an origin and denote position of the body with respect to origin as $x$. $x$ is positive when on the right side of origin and negative when it is on left of it. So, given x and origin, we can find exact position of the body and vice versa too- given position of body we can calculate x. For example, in the following figure, you can see value of $x$ at different positions of the body. Fill in the values of ? yourself.

Tracking Motion

Motion is change of position. Therefore, we analyse motion of a body between two positions of body in timeinterval between two positions. We are interested in knowing not only change in position(displacement), but also the rate at which position changed ( velocity) and whether velocity itself is changing and if yes at what rate ( acceleration). Hence, other than position, we define quantities related to motion as follows.

$ displacement = x_2 - x_1 \tag{1}$

$ velocity = \frac{dx}{dt} \tag{2}$

$ acceleration = \frac{dv}{dt} \tag{3}$

remember that all three quantities are vectors, but we have omitted vector notation after ensuring that direction shall be taken care of by using sign - a direction to right shall be labelled +ve and a direction to left shall be labelled negative.

Now, let us see how do we calculate these quantities. We shall begin with special cases.

Special case- velocity is constant

\(\frac{dx}{dt} = v \\ => dx = vdt \\\) integrating between time interval 0 to t and position $0$ and $x$, we get,

\[\int_{0}^{x} dx = \int_{0}^{t} vdt \\ \text{as velocity is constant,}\\ \int_{0}^{x} dx = v \int_{0}^{t} dt \\ => x = vt\]Special case- acceleration is constant

\(\frac{dv}{dt} = a \\ => dv = adt \\\) integrating between time interval 0 to t and velocity $u$ and $v$, we get,

\(\int_{u}^{v} dv = \int_{0}^{t} adt \\

\text{as acceleration is constant,}\\

\int_{u}^{v} dv = a \int_{0}^{t} dt \\

=> v - u = at\)

$=> v = u + at \tag{1}

$

\(dx/dt = v = u + at\\ dx = (u + at) dt\\ \int_0^x dx = \int_0^t (u + at) dt\) $x = ut + \frac{1}{2} at^2 \tag{2}$

You can see that all of the above equations have been derived with assumption that initial position is at x=0 and t=0 where v = u. Remember these when you use these formulae.

We can always assume initial position as 0 and initial time as 0. If not, then in the above formulae replace x with $x_2 - x_1$ and t with $t_2 - t_1$ ( derive yourself).

There is another relation in which t does not figure. You can calculate that by eliminiating t between (1) and (2), but we have a nicer method as follows. From chain rule of differentiation:-

\(dv/dt = a \\ => dv/dx * dx/dt = a\\ => dv/dx * v = a\\ => \int_{u}^{v} vdv = \int_0^x adx \\ => \frac{v^2}{2} \big]_u^v = ax\big]_0^x\\ => \frac{v^2-u^2}{2} = ax\\ => v^2 - u^2 = 2ax\) $v^2 = u^2 + 2ax\tag{3}$

Using these three equations,we can analyse all the situations easily in one dimension. However, remember always the assumptions behind these equations.

(1) Acceleration wherever present, is constant

(2) v = u and x = 0 at t = 0

Let us solve one problem.

Q1. A body starting from rest, first accelerates to reach a velocity of 3 m/s in 2 s and then accelerates further to higher acceleration to reach velocity of 10 m/s in next 3 sec. Find acceleration till t = 2s and after t = 2s?

Answer: The body starts from rest => t = 0, u = 0 The body has velocity of 3m/s at t = 2s from (3), $v = u + at $

\[2 = 0 + a_1 * 2 \\ a_1 = 2/2 = 1 m/s^2\]Now, let us see second interval, u = 3m/s and v = 10m/s after t=3s

hence, \(10 = 3 + a_2 * 3 \\ a_2 = (10-3)/3 = 7/3 = 2.3\)

Motion in two dimensions

to analyse motion in two dimensions, split the problem in two problems of single dimension. Take two axis orthogonal to each other X, Y and split quantities velocity, displacement, and acceleration into their components.

displacement vector $\vec{r}$ is split into $r_x$ or simply $x$ and $r_y$ or simply $y$

velocity vector $\vec{v}$ is split into $v_x$ and $v_y$

acceleration vector $\vec{a}$ is split into $a_x$ and $a_y$

and for each dimension, following formulae are applied:-

dx/dt = $v_x$

$dv_x/dt = a_x$

dy/dt = $v_y$

$dv_x/dt = a_x$

and in case, $a_x$ is constant, this reduces to,

$v_x = u_x + a_xt $

${v_x}^2 = {u_x}^2 + 2a_xx $

$x = u_xt + \frac{1}{2} a_x t^2$

and in case $a_y$ is constant,

$v_y = u_y + a_yt $

${v_y}^2 = {u_y}^2 + 2a_yy $

$y = u_yt + \frac{1}{2} a_y t^2$

Examples of motion in two dimension

Uniform Circular Motion

Suppose a body is moving in a circle with uniform speed. We did not say uniform velocity as velocity is changing due to change in direction. Velocity is always tangent to the path.